The Story Of The Man Who Had Nthing Except Speech Power-Adolf Hitler

Childhood

Adolf Hitler was born at around 6:30 p.m. on 20 April 1889 at the Gasthof zum Pommer, an inn in Braunau am Inn, Austria–Hungary, the fourth of six children to Alois Hitler and Klara Pölzl.When he was three years old, his family relocated to Kapuzinerstrasse 5[16] in Passau, Germany, where Hitler would acquire Lower Bavarian rather than Austrian as his lifelong native dialect.[17] In 1894, the family relocated to Leonding near Linz, then in June 1895, Alois retired to a small landholding at Hafeld near Lambach, where he tried his hand at farming and beekeeping. During this time, the young Hitler attended school in nearby Fischlham. As a child, he played "Cowboys and Indians" and, by his own account, became fixated on war after finding a picture book about the Franco-Prussian War among his father's belongings.[18]

His father's efforts at Hafeld ended in failure, and the family relocated to Lambach in 1897. Hitler attended a Catholic school located in an 11th-century Benedictine cloister, where the walls were engraved in a number of places with crests containing the symbol of the swastika.[19] It was in Lambach that the eight-year-old Hitler sang in the church choir, took singing lessons, and even entertained the fantasy of one day becoming a priest.[20] In 1898, the family returned permanently to Leonding.

His younger brother Edmund died of measles on 2 February 1900, causing permanent changes in Hitler. He went from a confident, outgoing boy who excelled in school, to a morose, detached, sullen boy who constantly battled his father and his teachers.[21]

Hitler was attached to his mother, though he had a troubled relationship with his father, who frequently beat him, especially in the years after Alois' retirement and disappointing farming efforts.[22] Alois wanted his son to follow in his footsteps as an Austrian customs official, and this became a huge source of conflict between them.[18] Despite his son's pleas to go to classical high school and become an artist, his father sent him to the Realschule in Linz, a technical high school of about 300 students, in September 1900. Hitler rebelled, and in Mein Kampf confessed to failing his first year in hopes that once his father saw "what little progress I was making at the technical school he would let me devote myself to the happiness I dreamed of." Alois never relented, however, and Hitler became even more bitter and rebellious.

German Nationalism quickly became an obsession for Hitler, and a way to rebel against his father, who proudly served the Austrian government. Most people who lived along the German-Austrian border considered themselves German-Austrians, but Hitler expressed loyalty only to Germany. In defiance of the Austrian monarchy, and his father who continually expressed loyalty to it, Hitler and his young friends liked to use the German greeting "Heil", and sing the German anthem "Deutschland Über Alles" instead of the Austrian Imperial anthem.[18]

After Alois' sudden death on 3 January 1903, Hitler's behaviour at the technical school became even more disruptive, and he was asked to leave. He enrolled at the Realschule in Steyr in 1904, but upon completing his second year, he and his friends went out for a night of celebration and drinking, and an intoxicated Hitler tore his school certificate into four pieces and used it as toilet paper. When someone turned the stained certificate in to the school's director, he "... gave him such a dressing-down that the boy was reduced to shivering jelly. It was probably the most painful and humiliating experience of his life."[23] Hitler was expelled, never to return to school again.

At age 15, Hitler took part in his First Holy Communion on Whitsunday, 22 May 1904, at the Linz Cathedral.[24] His sponsor was Emanuel Lugert, a friend of his late father.[25]

Early adulthood in Vienna and Munich

From 1905 on, Hitler lived a bohemian life in Vienna on an orphan's pension and support from his mother. He was rejected twice by the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna (1907–1908), citing "unfitness for painting", and was told his abilities lay instead in the field of architecture.[26] Following the school rector's recommendation, he too became convinced this was his path to pursue, yet he lacked the proper academic preparation for architecture school:In a few days I myself knew that I should some day become an architect. To be sure, it was an incredibly hard road; for the studies I had neglected out of spite at the Realschule were sorely needed. One could not attend the Academy's architectural school without having attended the building school at the Technic, and the latter required a high-school degree. I had none of all this. The fulfillment of my artistic dream seemed physically impossible.[27]On 21 December 1907, Hitler's mother died of breast cancer at age 47. Ordered by a court in Linz, Hitler gave his share of the orphans' benefits to his sister Paula. When he was 21, he inherited money from an aunt. He struggled as a painter in Vienna, copying scenes from postcards and selling his paintings to merchants and tourists. After being rejected a second time by the Academy of Arts, Hitler ran out of money. In 1909, he lived in a shelter for the homeless. By 1910, he had settled into a house for poor working men on Meldemannstraße. Another resident of the house, Reinhold Hanisch, sold Hitler's paintings until the two men had a bitter falling-out.[28]

Hitler said he first became an anti-Semite in Vienna,[27] which had a large Jewish community, including Orthodox Jews who had fled the pogroms in Russia. According to childhood friend August Kubizek, however, Hitler was a "confirmed anti-Semite" before he left Linz.[27] Vienna at that time was a hotbed of traditional religious prejudice and 19th century racism. Hitler may have been influenced by the occult writings of the anti-Semite Lanz von Liebenfels in his magazine Ostara; it is usually taken for granted that he read the publication (he recounts in Mein Kampf his conversion to anti-semitism being after reading some pamphlets) and he most likely did read it, although it is uncertain to what degree he was influenced by the anti-semitic occult work.[29]

There were very few Jews in Linz. In the course of centuries the Jews who lived there had become Europeanised in external appearance and were so much like other human beings that I even looked upon them as Germans. The reason why I did not then perceive the absurdity of such an illusion was that the only external mark which I recognized as distinguishing them from us was the practice of their strange religion. As I thought that they were persecuted on account of their faith my aversion to hearing remarks against them grew almost into a feeling of abhorrence. I did not in the least suspect that there could be such a thing as a systematic antisemitism. Once, when passing through the inner City, I suddenly encountered a phenomenon in a long caftan and wearing black side-locks. My first thought was: Is this a Jew? They certainly did not have this appearance in Linz. I carefully watched the man stealthily and cautiously but the longer I gazed at the strange countenance and examined it feature by feature, the more the question shaped itself in my brain: Is this a German?[27]If this account is true, Hitler apparently did not act on his new belief. He often was a guest for dinner in a noble Jewish house, and he interacted well with Jewish merchants who tried to sell his paintings.[30]

Hitler may also have been influenced by Martin Luther's On the Jews and their Lies. In Mein Kampf, Hitler refers to Martin Luther as a great warrior, a true statesman, and a great reformer, alongside Richard Wagner and Frederick the Great.[31] Wilhelm Röpke, writing after the Holocaust, concluded that "without any question, Lutheranism influenced the political, spiritual and social history of Germany in a way that, after careful consideration of everything, can be described only as fateful."[32][33]

Hitler claimed that Jews were enemies of the Aryan race. He held them responsible for Austria's crisis. He also identified certain forms of socialism and Bolshevism, which had many Jewish leaders, as Jewish movements, merging his antisemitism with anti-Marxism. Later, blaming Germany's military defeat in World War I on the 1918 revolutions, he considered Jews the culprits of Imperial Germany's downfall and subsequent economic problems as well.

Hitler received the final part of his father's estate in May 1913 and moved to Munich. He wrote in Mein Kampf that he had always longed to live in a "real" German city. In Munich, he became more interested in architecture and, he says, the writings of Houston Stewart Chamberlain. Moving to Munich also helped him escape military service in Austria for a time, but the Munich police (acting in cooperation with the Austrian authorities) eventually arrested him. After a physical exam and a contrite plea, he was deemed unfit for service and allowed to return to Munich. However, when Germany entered World War I in August 1914, he petitioned King Ludwig III of Bavaria for permission to serve in a Bavarian regiment. This request was granted, and Adolf Hitler enlisted in the Bavarian army.[34]

World War I

Main article: Military career of Adolf Hitler

Hitler served in France and Belgium in the 16th Bavarian Reserve Regiment, on the Western Front as a regimental runner. He was present at a number of major battles on the Western Front, including the First Battle of Ypres, the Battle of the Somme, the Battle of Arras and the Battle of Passchendaele.[35]Hitler was twice decorated for bravery. He received the relatively common Iron Cross, Second Class, in 1914 and Iron Cross, First Class, in 1918, an honour rarely given to a Gefreiter.[36] Yet because the regimental staff thought Hitler lacked leadership skills, he was never promoted to Unteroffizier (equivalent to a British corporal). According to Weber, Hitler's First Class Iron Cross was recommended by Hugo Gutmann, a Jewish List adjutant, and this rarer award was commonly awarded to those posted to regimental headquarters, such as Hitler, who had more contact with more senior officers than combat soldiers.[37]

Hitler's duties at regimental headquarters gave him time to pursue his artwork. He drew cartoons and instructional drawings for an army newspaper. In 1916, he was wounded in either the groin area[38] or the left thigh[39] during the Battle of the Somme, but returned to the front in March 1917. He received the Wound Badge later that year. German historian and author, Sebastian Haffner, referring to Hitler's experience at the front, suggests that he had at least some understanding of the military.

On 15 October 1918, Hitler was admitted to a field hospital, temporarily blinded by a mustard gas attack. The English psychologist David Lewis and Bernhard Horstmann suggest the blindness may have been the result of a conversion disorder (then known as "hysteria").[40] In fact, Hitler said it was during this experience that he became convinced the purpose of his life was to "save Germany." Some scholars, notably Lucy Dawidowicz,[41] argue that an intention to exterminate Europe's Jews was fully formed in Hitler's mind at this time, though he probably had not thought through how it could be done. Most historians think the decision was made in 1941, and some think it came as late as 1942.

Hitler had long admired Germany, and during the war he had become a passionate German patriot, although he did not become a German citizen until 1932. Hitler found the war to be "the greatest of all experiences" and afterwards he was praised by a number of his commanding officers for his bravery.[42] He was shocked by Germany's capitulation in November 1918 even while the German army still held enemy territory.[43] Like many other German nationalists, Hitler believed in the Dolchstoßlegende ("dagger-stab legend") which claimed that the army, "undefeated in the field," had been "stabbed in the back" by civilian leaders and Marxists back on the home front. These politicians were later dubbed the November Criminals.

The Treaty of Versailles deprived Germany of various territories, demilitarised the Rhineland and imposed other economically damaging sanctions. The treaty re-created Poland, which even moderate Germans regarded as an outrage. The treaty also blamed Germany for all the horrors of the war, something which major historians such as John Keegan now consider at least in part to be victor's justice; most European nations in the run-up to World War I had become increasingly militarised and were eager to fight. The culpability of Germany was used as a basis to impose reparations on Germany (the amount was repeatedly revised under the Dawes Plan, the Young Plan, and the Hoover Moratorium). Germany in turn perceived the treaty, especially Article 231 on the German responsibility for the war, as a humiliation. For example, there was a nearly total demilitarisation of the armed forces, allowing Germany only six battleships, no submarines, no air force, an army of 100,000 without conscription and no armoured vehicles. The treaty was an important factor in both the social and political conditions encountered by Hitler and his Nazis as they sought power. Hitler and his party used the signing of the treaty by the "November Criminals" as a reason to build up Germany so that it could never happen again. He also used the "November Criminals" as scapegoats, although at the Paris peace conference, these politicians had had very little choice in the matter.

Entry into politics

Main article: Adolf Hitler's political views

After World War I, Hitler remained in the army and returned to Munich, where he – in contrast to his later declarations – attended the funeral march for the murdered Bavarian prime minister Kurt Eisner.[44] After the suppression of the Bavarian Soviet Republic, he took part in "national thinking" courses organized by the Education and Propaganda Department (Dept Ib/P) of the Bavarian Reichswehr Group, Headquarters 4 under Captain Karl Mayr. Scapegoats were found in "international Jewry", communists, and politicians across the party spectrum, especially the parties of the Weimar Coalition.In July 1919, Hitler was appointed a Verbindungsmann (police spy) of an Aufklärungskommando (Intelligence Commando) of the Reichswehr, both to influence other soldiers and to infiltrate a small party, the German Workers' Party (DAP). During his inspection of the party, Hitler was impressed with founder Anton Drexler's anti-semitic, nationalist, anti-capitalist and anti-Marxist ideas, which favoured a strong active government, a "non-Jewish" version of socialism and mutual solidarity of all members of society. Drexler was impressed with Hitler's oratory skills and invited him to join the party. Hitler joined DAP on 12 September 1919[45] and became the party's 55th member.[46] His actual membership number was 555 (the 500 was added to make the group appear larger) but later the number was reduced to create the impression that Hitler was one of the founding members.[47] He was also made the seventh member of the executive committee.[48] Years later, he claimed to be the party's seventh overall member, but it has been established that this claim is false.[49]

Here Hitler met Dietrich Eckart, one of the early founders of the party and member of the occult Thule Society.[50] Eckart became Hitler's mentor, exchanging ideas with him, teaching him how to dress and speak, and introducing him to a wide range of people. Hitler thanked Eckart by paying tribute to him in the second volume of Mein Kampf. To increase the party's appeal, the party changed its name to the Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or National Socialist German Workers Party (abbreviated NSDAP).

Hitler was discharged from the army in March 1920 and with his former superiors' continued encouragement began participating full time in the party's activities. By early 1921, Hitler was becoming highly effective at speaking in front of large crowds. In February, Hitler spoke before a crowd of nearly six thousand in Munich. To publicize the meeting, he sent out two truckloads of party supporters to drive around with swastikas, cause a commotion and throw out leaflets, their first use of this tactic. Hitler gained notoriety outside of the party for his rowdy, polemic speeches against the Treaty of Versailles, rival politicians (including monarchists, nationalists and other non-internationalist socialists) and especially against Marxists and Jews.

The NSDAP[51] was centred in Munich, a hotbed of German nationalists who included Army officers determined to crush Marxism and undermine the Weimar Republic. Gradually they noticed Hitler and his growing movement as a suitable vehicle for their goals. Hitler traveled to Berlin to visit nationalist groups during the summer of 1921, and in his absence there was a revolt among the DAP leadership in Munich.

The party was run by an executive committee whose original members considered Hitler to be overbearing. They formed an alliance with a group of socialists from Augsburg. Hitler rushed back to Munich and countered them by tendering his resignation from the party on 11 July 1921. When they realized the loss of Hitler would effectively mean the end of the party, he seized the moment and announced he would return on the condition that he replace Drexler as party chairman, with unlimited powers. Infuriated committee members (including Drexler) held out at first. Meanwhile an anonymous pamphlet appeared entitled Adolf Hitler: Is he a traitor?, attacking Hitler's lust for power and criticizing the violent men around him. Hitler responded to its publication in a Munich newspaper by suing for libel and later won a small settlement.

The executive committee of the NSDAP eventually backed down and Hitler's demands were put to a vote of party members. Hitler received 543 votes for and only one against. At the next gathering on 29 July 1921, Adolf Hitler was introduced as Führer of the National Socialist German Workers' Party, marking the first time this title was publicly used.

Hitler's beer hall oratory, attacking Jews, social democrats, liberals, reactionary monarchists, capitalists and communists, began attracting adherents. Early followers included Rudolf Hess, the former air force pilot Hermann Göring, and the army captain Ernst Röhm, who eventually became head of the Nazis' paramilitary organization the SA (Sturmabteilung, or "Storm Division"), which protected meetings and attacked political opponents. As well, Hitler assimilated independent groups, such as the Nuremberg-based Deutsche Werkgemeinschaft, led by Julius Streicher, who became Gauleiter of Franconia. Hitler attracted the attention of local business interests, was accepted into influential circles of Munich society, and became associated with wartime General Erich Ludendorff during this time.

Beer Hall Putsch

Main article: Beer Hall Putsch

Encouraged by this early support, Hitler decided to use Ludendorff as a front in an attempted coup later known as the "Beer Hall Putsch" (sometimes as the "Hitler Putsch" or "Munich Putsch"). The Nazi Party had copied Italy's fascists in appearance and had adopted some of their policies, and in 1923, Hitler wanted to emulate Benito Mussolini's "March on Rome" by staging his own "Campaign in Berlin". Hitler and Ludendorff obtained the clandestine support of Gustav von Kahr, Bavaria's de facto ruler, along with leading figures in the Reichswehr and the police. As political posters show, Ludendorff, Hitler and the heads of the Bavarian police and military planned on forming a new government.On 8 November 1923, Hitler and the SA stormed a public meeting headed by Kahr in the Bürgerbräukeller, a large beer hall in Munich. He declared that he had set up a new government with Ludendorff and demanded, at gunpoint, the support of Kahr and the local military establishment for the destruction of the Berlin government.[52] Kahr withdrew his support and fled to join the opposition to Hitler at the first opportunity.[53] The next day, when Hitler and his followers marched from the beer hall to the Bavarian War Ministry to overthrow the Bavarian government as a start to their "March on Berlin", the police dispersed them. Sixteen NSDAP members were killed.[54]

Hitler fled to the home of Ernst Hanfstaengl and contemplated suicide; Hanfstaengl's wife Helene talked him out of it. He was soon arrested for high treason. Alfred Rosenberg became temporary leader of the party. During Hitler's trial, he was given almost unlimited time to speak, and his popularity soared as he voiced nationalistic sentiments in his defence speech. A Munich personality thus became a nationally known figure. On 1 April 1924, Hitler was sentenced to five years' imprisonment at Landsberg Prison. Hitler received favoured treatment from the guards and had much fan mail from admirers. He was pardoned and released from jail on 20 December 1924, by order of the Bavarian Supreme Court on 19 December, which issued its final rejection of the state prosecutor's objections to Hitler's early release.[55] Including time on remand, he had served little more than one year of his sentence.[56]

On 28 June 1925, Hitler wrote a letter from Uffing to the editor of The Nation in New York City complaining of the length of his sentence at "Sandberg a. S." [sic], where he claimed his privileges had been extensively revoked.[57]

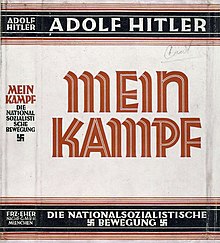

Mein Kampf

Main article: Mein Kampf

While at Landsberg, he dictated most of the first volume of Mein Kampf (My Struggle, originally entitled Four and a Half Years of Struggle against Lies, Stupidity, and Cowardice) to his deputy Rudolf Hess.[56] The book, dedicated to Thule Society member Dietrich Eckart, was an autobiography and an exposition of his ideology. Mein Kampf was influenced by The Passing of the Great Race by Madison Grant, which Hitler called "my Bible."[58] It was published in two volumes in 1925 and 1926, selling about 240,000 copies between 1925 and 1934. By the end of the war, about 10 million copies had been sold or distributed (newlyweds and soldiers received free copies). The copyright of Mein Kampf in Europe is claimed by the Free State of Bavaria and scheduled to end on 31 December 2015. Reproductions in Germany are authorized only for scholarly purposes and in heavily commented form.Rebuilding of the party

At the time of Hitler's release, the political situation in Germany had calmed and the economy had improved, which hampered Hitler's opportunities for agitation. Though the "Hitler Putsch" had given Hitler some national prominence, Munich remained his party's mainstay.

The NSDAP and its organs were banned in Bavaria after the collapse of the putsch. Hitler convinced Heinrich Held, Prime Minister of Bavaria, to lift the ban, based on representations that the party would now only seek political power through legal means. Even though the ban on the NSDAP was removed effective 16 February 1925,[59] Hitler incurred a new ban on public speaking as a result of an inflammatory speech. Since Hitler was banned from public speeches, he appointed Gregor Strasser, who in 1924 had been elected to the Reichstag, as Reichsorganisationsleiter, authorizing him to organize the party in northern Germany. Strasser, joined by his younger brother Otto and Joseph Goebbels, steered an increasingly independent course, emphasizing the socialist element in the party's programme. The Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Gauleiter Nord-West became an internal opposition, threatening Hitler's authority, but this faction was defeated at the Bamberg Conference in 1926, during which Goebbels joined Hitler.

After this encounter, Hitler centralized the party even more and asserted the Führerprinzip ("Leader principle") as the basic principle of party organization. Leaders were not elected by their group, but were rather appointed by their superior, answering to them while demanding unquestioning obedience from their inferiors. Consistent with Hitler's disdain for democracy, all power and authority devolved from the top down.

A key element of Hitler's appeal was his ability to evoke a sense of offended national pride caused by the Treaty of Versailles imposed on the defeated German Empire by the Western Allies. Germany had lost economically important territory in Europe along with its colonies, and in admitting to sole responsibility for the war had agreed to pay a huge reparations bill totaling 132 billion marks. Most Germans bitterly resented these terms, but early Nazi attempts to gain support by blaming these humiliations on "international Jewry" were not particularly successful with the electorate. The party learned quickly, and soon a more subtle propaganda emerged, combining antisemitism with an attack on the failures of the "Weimar system" and the parties supporting it.

Having failed in overthrowing the Republic by a coup, Hitler pursued a "strategy of legality": this meant formally adhering to the rules of the Weimar Republic until he had legally gained power. He would then use the institutions of the Weimar Republic to destroy it and establish himself as dictator. Some party members, especially in the paramilitary SA, opposed this strategy; Röhm and others ridiculed Hitler as "Adolphe Legalité".

Rise to power

Main article: Adolf Hitler's rise to power

Date | Votes | Percentage | Seats in Reichstag | Background |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| May 1924 | 1,918,300 | 6.5 | 32 | Hitler in prison |

| December 1924 | 907,300 | 3.0 | 14 | Hitler is released from prison |

| May 1928 | 810,100 | 2.6 | 12 | |

| September 1930 | 6,409,600 | 18.3 | 107 | After the financial crisis |

| July 1932 | 13,745,800 | 37.4 | 230 | After Hitler was candidate for presidency |

| November 1932 | 11,737,000 | 33.1 | 196 | |

| March 1933 | 17,277,000 | 43.9 | 288 | During Hitler's term as Chancellor of Germany |

Brüning Administration

The political turning point for Hitler came when the Great Depression hit Germany in 1930. The Weimar Republic had never been firmly rooted and was openly opposed by right-wing conservatives (including monarchists), communists and the Nazis. As the parties loyal to the democratic, parliamentary republic found themselves unable to agree on counter-measures, their grand coalition broke up and was replaced by a minority cabinet. The new Chancellor, Heinrich Brüning of the Roman Catholic Centre Party, lacking a majority in parliament, had to implement his measures through the president's emergency decrees. Tolerated by the majority of parties, this rule by decree would become the norm over a series of unworkable parliaments and paved the way for authoritarian forms of government.[60]

The Reichstag's initial opposition to Brüning's measures led to premature elections in September 1930. The republican parties lost their majority and their ability to resume the grand coalition, while the Nazis suddenly rose from relative obscurity to win 18.3% of the vote along with 107 seats. In the process, they jumped from the ninth-smallest party in the chamber to the second largest.[61]

In September–October 1930, Hitler appeared as a major defence witness at the trial in Leipzig of two junior Reichswehr officers charged with membership of the Nazi Party, which at that time was forbidden to Reichswehr personnel.[62] The two officers, Leutnants Richard Scheringer and Hans Ludin, admitted quite openly to Nazi Party membership, and used as their defence that the Nazi Party membership should not be forbidden to those serving in the Reichswehr.[63] When the Prosecution argued that the Nazi Party was a dangerous revolutionary force, one of the defence lawyers, Hans Frank had Hitler brought to the stand to prove that the Nazi Party was a law-abiding party.[63] During his testimony, Hitler insisted that his party was determined to come to power legally, that the phrase "National Revolution" was only to be interpreted "politically", and that his Party was a friend, not an enemy of the Reichswehr.[64] Hitler's testimony of 25 September 1930 won him many admirers within the ranks of the officer corps.[65]

Brüning's measures of budget consolidation and financial austerity brought little economic improvement and were extremely unpopular.[66] Under these circumstances, Hitler appealed to the bulk of German farmers, war veterans and the middle class, who had been hard-hit by both the inflation of the 1920s and the unemployment of the Depression.[67] In September 1931, Hitler's niece Geli Raubal was found dead in her bedroom in his Munich apartment (his half-sister Angela and her daughter Geli had been with him in Munich since 1929), an apparent suicide. Geli, who was believed to be in some sort of romantic relationship with Hitler, was 19 years younger than he was and had used his gun. His niece's death is viewed as a source of deep, lasting pain for him.[68]

In 1932, Hitler intended to run against the aging President Paul von Hindenburg in the scheduled presidential elections. His 27 January 1932 speech to the Industry Club in Düsseldorf won him, for the first time, support from a broad swath of Germany's most powerful industrialists.[69] Though Hitler had left Austria in 1913 and had formally renounced his Austrian citizenship on 7 April 1925, he still had not acquired German citizenship and hence could not run for public office. For almost seven years Hitler was stateless and faced the risk of deportation from Germany.[70] On 25 February, however, the Nazi interior minister of Brunswick (the Nazis were part of a right-wing coalition governing the state) appointed Hitler as administrator for the state's delegation to the Reichsrat in Berlin. This appointment made Hitler a citizen of Brunswick.[71] In those days, the states conferred citizenship, so this automatically made Hitler a citizen of Germany as well and thus eligible to run for president.[72]

The new German citizen ran against Hindenburg, who was supported by a broad range of nationalist, monarchist, Catholic, republican and even social democratic parties. Another candidate was a Communist and member of a fringe right-wing party. Hitler's campaign was called "Hitler über Deutschland" (Hitler over Germany).[73] The name had a double meaning; besides a reference to his dictatorial ambitions, it referred to the fact that he campaigned by aircraft.[73] Hitler came in second on both rounds, attaining more than 35% of the vote during the second one in April. Although he lost to Hindenburg, the election established Hitler as a realistic alternative in German politics.[74]

Appointment as Chancellor

| This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding reliable references. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (April 2009) |

Hitler from a window of the Chancellory receiving an ovation at his inauguration as Chancellor, 30 January 1933

On the morning of 30 January 1933, in Hindenburg's office, Adolf Hitler was sworn in as Chancellor during what some observers later described as a brief and simple ceremony. His first speech as Chancellor took place on 10 February. The Nazis' seizure of power subsequently became known as the Machtergreifung or Machtübernahme.

Reichstag fire and the March elections

Having become Chancellor, Hitler foiled all attempts by his opponents to gain a majority in parliament. Because no single party could gain a majority, Hitler persuaded President Hindenburg to dissolve the Reichstag again. Elections were scheduled for early March, but on 27 February 1933, the Reichstag building was set on fire.[77] Since a Dutch independent communist was found in the building, the fire was blamed on a communist plot. The government reacted with the Reichstag Fire Decree of 28 February which suspended basic rights, including habeas corpus. Under the provisions of this decree, the German Communist Party (KPD) and other groups were suppressed, and Communist functionaries and deputies were arrested, forced to flee, or murdered.Campaigning continued, with the Nazis making use of paramilitary violence, anti-communist hysteria, and the government's resources for propaganda. On election day, 6 March, the NSDAP increased its result to 43.9% of the vote, remaining the largest party, but its victory was marred by its failure to secure an absolute majority, necessitating maintaining a coalition with the DNVP.[78]

"Day of Potsdam" and the Enabling Act

| This section does not cite any references or sources. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (April 2009) |

Because of the Nazis' failure to obtain a majority on their own, Hitler's government confronted the newly elected Reichstag with the Enabling Act that would have vested the cabinet with legislative powers for a period of four years. Though such a bill was not unprecedented, this act was different since it allowed for deviations from the constitution. Since the bill required a ⅔ majority in order to pass, the government needed the support of other parties. The position of the Centre Party, the third largest party in the Reichstag, turned out to be decisive: under the leadership of Ludwig Kaas, the party decided to vote for the Enabling Act. It did so in return for the government's oral guarantees regarding the Church's liberty, the concordats signed by German states and the continued existence of the Centre Party.

On 23 March, the Reichstag assembled in a replacement building under extremely turbulent circumstances. Some SA men served as guards within while large groups outside the building shouted slogans and threats toward the arriving deputies. Kaas announced that the Centre Party would support the bill with "concerns put aside," while Social Democrat Otto Wels denounced the act in his speech. At the end of the day, all parties except the Social Democrats voted in favour of the bill. The Communists, as well as some Social Democrats, were barred from attending. The Enabling Act, combined with the Reichstag Fire Decree, transformed Hitler's government into a legal dictatorship.

Removal of remaining limits

| “ | At the risk of appearing to talk nonsense I tell you that the Nazi movement will go on for 1,000 years! ... Don't forget how people laughed at me 15 years ago when I declared that one day I would govern Germany. They laugh now, just as foolishly, when I declare that I shall remain in power! | ” |

—Adolf Hitler to a British correspondent in Berlin, June 1934[79] | ||

Hitler used the SA paramilitary to push Hugenberg into resigning, and proceeded to politically isolate Vice-Chancellor Papen. Because the SA's demands for political and military power caused much anxiety among military and political leaders, Hitler used allegations of a plot by the SA leader Ernst Röhm to purge the SA's leadership during the Night of the Long Knives. As well, opponents unconnected with the SA were murdered, notably Gregor Strasser and former Chancellor Kurt von Schleicher.[81]

President Paul von Hindenburg died on 2 August 1934. Rather than call new elections as required by the constitution, Hitler's cabinet passed a law proclaiming the presidency vacant and transferred the role and powers of the head of state to Hitler as Führer und Reichskanzler (leader and chancellor). This action effectively removed the last legal remedy by which Hitler could be dismissed – and with it, nearly all institutional checks and balances on his power.

On 19 August a plebiscite approved the merger of the presidency with the chancellorship winning 84.6% of the electorate.[82][83] This action technically violated both the constitution and the Enabling Act. The constitution had been amended in 1932 to make the president of the High Court of Justice, not the chancellor, acting president until new elections could be held. The Enabling Act specifically barred Hitler from taking any action that tampered with the presidency. However, no one dared object.

As head of state, Hitler now became Supreme Commander of the armed forces. When it came time for the soldiers and sailors to swear the traditional loyalty oath, it had been altered into an oath of personal loyalty to Hitler. Normally, soldiers and sailors swear loyalty to the holder of the office of supreme commander/commander-in-chief, not a specific person.[84]

In 1938, two scandals resulted in Hitler bringing the Armed Forces under his control. Hitler forced the resignation of his War Minister (formerly Defense Minister), Werner von Blomberg, after evidence surfaced that Blomberg's new wife had a criminal past. Prior to removing Blomberg, Hitler and his clique removed army commander Werner von Fritsch on suspicion of homosexuality.[85] Hitler replaced the Ministry of War with the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (High Command of the Armed Forces, or OKW), headed by the pliant General Wilhelm Keitel. More importantly, Hitler announced he was assuming personal command of the armed forces. He took over Blomberg's other old post, that of Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces, for himself. He was already Supreme Commander by virtue of holding the powers of the president. The next day, the newspapers announced, "Strongest concentration of powers in Führer's hands!"

Third Reich

Main article: Nazi Germany

Having secured supreme political power, Hitler went on to gain public support by convincing most Germans he was their saviour from the economic Depression, the Versailles treaty, communism, the "Judeo-Bolsheviks", and other "undesirable" minorities. The Nazis eliminated opposition through a process known as Gleichschaltung ("bringing into line").Economy and culture

Hitler oversaw one of the greatest expansions of industrial production and civil improvement Germany had ever seen, mostly based on debt flotation (refinancing long term debts into cheaper short term debt) and expansion of the military. Nazi policies toward women strongly encouraged them to stay at home to bear children and keep house. In a September 1934 speech to the National Socialist Women's Organization, Adolf Hitler argued that for the German woman her "world is her husband, her family, her children, and her home." This policy was reinforced by bestowing the Cross of Honor of the German Mother on women bearing four or more babies. The unemployment rate was cut substantially, mostly through arms production and sending women home so that men could take their jobs. Given this, claims that the German economy achieved near full employment are at least partly artefacts of propaganda from the era. Much of the financing for Hitler's reconstruction and rearmament came from currency manipulation by Hjalmar Schacht, including the clouded credits through the Mefo bills.Hitler oversaw one of the largest infrastructure-improvement campaigns in German history, with the construction of dozens of dams, autobahns, railroads, and other civil works. This revitalising of industry and infrastructure came at the expense of the overall standard of living, at least for those not affected by the chronic unemployment of the later Weimar Republic, since wages were slightly reduced in pre-World War II years, despite a 25% increase in the cost of living.[86] Laborers and farmers, the traditional voters of the NSDAP, however, saw an increase in their standard of living.

Hitler's government sponsored architecture on an immense scale, with Albert Speer becoming famous as the first architect of the Reich. While important as an architect in implementing Hitler's classicist reinterpretation of German culture, Speer proved much more effective as armaments minister during the last years of World War II. In 1936, Berlin hosted the summer Olympic games, which were opened by Hitler and choreographed to demonstrate Aryan superiority over all other races, achieving mixed results.

Although Hitler made plans for a Breitspurbahn ("broad gauge railroad network"), they were preempted by World War II. Had the railroad been built, its gauge would have been three metres, even wider than the old Great Western Railway of Britain.

Hitler contributed slightly to the design of the car that later became the Volkswagen Beetle and charged Ferdinand Porsche with its design and construction.[87] Production was deferred because of the war.

On 20 April 1939, a lavish celebration was held in honour of Hitler's 50th birthday, featuring military parades, visits from foreign dignitaries, thousands of flaming torches and Nazi banners.[88]

An important historical debate about Hitler's economic policies concerns the "modernization" issue. Historians such as David Schoenbaum and Henry Ashby Turner have argued that social and economic polices under Hitler were modernization carried out in pursuit of anti-modern goals.[89] Other groups of historians centred around Rainer Zitelmann have contended that Hitler had a deliberate strategy of pursuing a revolutionary modernization of German society.[90]

In his first four years of government the number of unemployed dropped from 6 million to 900 thousand people, the gross national product grew 102%, he doubled the per capita income, augmented companies' profits from 175 million to 5 billion reichsmarks and reduced hyperinflation to a maximum of 25% a year.[citation needed]

Rearmament and new alliances

| This section may be too long to read and navigate comfortably. Please consider moving more of the content into sub-articles and using this article for a summary of the key points of the subject. (April 2010) |

In a meeting with his leading generals and admirals on 3 February 1933, Hitler spoke of "conquest of Lebensraum in the East and its ruthless Germanisation" as his ultimate foreign policy objectives.[91] In March 1933, the first major statement of German foreign policy aims appeared with the memo submitted to the German Cabinet by the State Secretary at the Auswärtiges Amt (Foreign Office), Prince Bernhard Wilhelm von Bülow (not to be confused with his more famous uncle, the former Chancellor Bernhard von Bülow), which advocated Anschluss with Austria, the restoration of the frontiers of 1914, the rejection of the Part V of Versailles, the return of the former German colonies in Africa, and a German zone of influence in Eastern Europe as goals for the future. Hitler found the goals in Bülow's memo to be too modest.[92] In March 1933, to resolve the deadlock between the French demand for sécurité ("security") and the German demand for gleichberechtigung ("equality of armaments") at the World Disarmament Conference in Geneva, Switzerland, the British Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald presented the compromise "MacDonald Plan". Hitler endorsed the "MacDonald Plan", correctly guessing that nothing would come of it, and that in the interval he could win some goodwill in London by making his government appear moderate, and the French obstinate.[93]

In May 1933, Hitler met with Herbert von Dirksen, the German Ambassador in Moscow. Dirksen advised the Führer that he was allowing relations with the Soviet Union to deteriorate to an unacceptable extent, and advised to take immediate steps to repair relations with the Soviets.[94] Much to Dirksen's intense disappointment, Hitler informed that he wished for an anti-Soviet understanding with Poland, which Dirksen protested implied recognition of the German-Polish border, leading Hitler to state he was after much greater things than merely overturning the Treaty of Versailles.[95]

In June 1933, Hitler was forced to disavow Alfred Hugenberg of the German National People's Party, who while attending the London World Economic Conference put forth a programme of colonial expansion in both Africa and Eastern Europe, which created a major storm abroad.[96] Speaking to the Burgermeister of Hamburg in 1933, Hitler commented that Germany required several years of peace before it could be sufficiently rearmed enough to risk a war, and until then a policy of caution was called for.[97] In his "peace speeches" of 17 May 1933, 21 May 1935, and 7 March 1936, Hitler stressed his supposed peaceful goals and a willingness to work within the international system.[98] In private, Hitler's plans were something less than peaceful. At the first meeting of his Cabinet in 1933, Hitler placed military spending ahead of unemployment relief, and indeed was only prepared to spend money on the latter if the former was satisfied first.[99] When the president of the Reichsbank, the former Chancellor Dr. Hans Luther, offered the new government the legal limit of 100 million Reichmarks to finance rearmament, Hitler found the sum too low, and sacked Luther in March 1933 to replace him with Hjalmar Schacht, who during the next five years was to advance 12 billion Reichmarks worth of "Mefo-bills" to pay for rearmament.[100]

A major initiative in Hitler's foreign policy in his early years was to create an alliance with Britain. In the 1920s, Hitler wrote that a future National Socialist foreign policy goal was "the destruction of Russia with the help of England."[101] In May 1933, Alfred Rosenberg in his capacity as head of the Nazi Party's Aussenpolitisches Amt (Foreign Political Office) visited London as part of a disastrous effort to win an alliance with Britain.[102] In October 1933, Hitler pulled Germany out of both the League of Nations and World Disarmament Conference after his Foreign Minister Baron Konstantin von Neurath made it appear to world public opinion that the French demand for sécurité was the principal stumbling block.[103]

In line with the views he advocated in Mein Kampf and Zweites Buch about the necessity of building an Anglo-German alliance, Hitler, in a meeting in November 1933 with the British Ambassador, Sir Eric Phipps, offered a scheme in which Britain would support a 300,000-strong German Army in exchange for a German "guarantee" of the British Empire.[104] In response, the British stated a 10-year waiting period would be necessary before Britain would support an increase in the size of the German Army.[104] A more successful initiative in foreign policy occurred with relations with Poland. In spite of intense opposition from the military and the Auswärtiges Amt who preferred closer ties with the Soviet Union, Hitler, in the fall of 1933 opened secret talks with Poland that were to lead to the German–Polish Non-Aggression Pact of January 1934.[103]

In February 1934, Hitler met with the British Lord Privy Seal, Sir Anthony Eden, and hinted strongly that Germany already possessed an Air Force, which had been forbidden by the Treaty of Versailles.[105] In the fall of 1934, Hitler was seriously concerned over the dangers of inflation damaging his popularity.[106] In a secret speech given before his Cabinet on 5 November 1934, Hitler stated he had "given the working class his word that he would allow no price increases. Wage-earners would accuse him of breaking his word if he did not act against the rising prices. Revolutionary conditions among the people would be the further consequence."[106]

Although a secret German armaments programme had been on-going since 1919, in March 1935, Hitler rejected Part V of the Versailles treaty by publicly announcing that the German army would be expanded to 600,000 men (six times the number stipulated in the Treaty of Versailles), introducing an Air Force (Luftwaffe) and increasing the size of the Navy (Kriegsmarine). Britain, France, Italy and the League of Nations quickly condemned these actions. However, after re-assurances from Hitler that Germany was only interested in peace, no country took any action to stop this development and German re-armament continued. Later in March 1935, Hitler held a series of meetings in Berlin with the British Foreign Secretary Sir John Simon and Eden, during which he successfully evaded British offers for German participation in a regional security pact meant to serve as an Eastern European equivalent of the Locarno pact while the two British ministers avoided taking up Hitler's offers of alliance.[107] During his talks with Simon and Eden, Hitler first used what he regarded as the brilliant colonial negotiating tactic, when Hitler parlayed an offer from Simon to return to the League of Nations by demanding the return of the former German colonies in Africa.[108]

Starting in April 1935, disenchantment with how the Third Reich had developed in practice as opposed to what been promised led many in the Nazi Party, especially the Alte Kämpfer (Old Fighters; i.e., those who joined the Party before 1930, and who tended to be the most ardent anti-Semitics in the Party), and the SA into lashing out against Germany's Jewish minority as a way of expressing their frustrations against a group that the authorities would not generally protect.[109] The rank and file of the Party were most unhappy that two years into the Third Reich, and despite countless promises by Hitler prior to 1933, no law had been passed banning marriage or sex between those Germans belonging to the "Aryan" and Jewish "races". A Gestapo report from the spring of 1935 stated that the rank and file of the Nazi Party would "set in motion by us from below," a solution to the "Jewish problem," "that the government would then have to follow."[110] As a result, Nazi Party activists and the SA started a major wave of assaults, vandalism and boycotts against German Jews.[111]

On 18 June 1935, the Anglo-German Naval Agreement (AGNA) was signed in London which allowed for increasing the allowed German tonnage up to 35% of that of the British navy. Hitler called the signing of the AGNA "the happiest day of his life" as he believed the agreement marked the beginning of the Anglo-German alliance he had predicted in Mein Kampf.[112] This agreement was made without consulting either France or Italy, directly undermining the League of Nations and put the Treaty of Versailles on the path towards irrelevance.[113] After the signing of the A.G.N.A., in June 1935 Hitler ordered the next step in the creation of an Anglo-German alliance: taking all the societies demanding the restoration of the former German African colonies and coordinating (Gleichschaltung) them into a new Reich Colonial League (Reichskolonialbund) which over the next few years waged an extremely aggressive propaganda campaign for colonial restoration.[114] Hitler had no real interest in the former German African colonies. In Mein Kampf, Hitler had excoriated the Imperial German government for pursuing colonial expansion in Africa prior to 1914 on the grounds that the natural area for Lebensraum was Eastern Europe, not Africa.[115] It was Hitler's intention to use colonial demands as a negotiating tactic that would see a German "renunciation" of colonial claims in exchange for Britain making an alliance with the Reich on German terms.[116]

In the summer of 1935, Hitler was informed that, between inflation and the need to use foreign exchange to buy raw materials Germany lacked for rearmament, there were only 5 million Reichmarks available for military expenditure, and a pressing need for some 300,000 Reichmarks/day to prevent food shortages.[117] In August 1935, Dr. Hjalmar Schacht advised Hitler that the wave of anti-Semitic violence was interfering with the workings of the economy, and hence rearmament.[118] Following Dr. Schacht's complaints, plus reports that the German public did not approve of the wave of anti-Semitic violence, and that continuing police toleration of the violence was hurting the regime's popularity with the wider public, Hitler ordered a stop to "individual actions" against German Jews on 8 August 1935.[118] From Hitler's perspective, it was imperative to bring in harsh new anti-Semitic laws as a consolation prize for those Party members who were disappointed with Hitler's halt order of 8 August, especially because Hitler had only reluctantly given the halt order for pragmatic reasons, and his sympathies were with the Party radicals.[118] The annual Nazi Party Rally held at Nuremberg in September 1935 was to feature the first session of the Reichstag held at that city since 1543. Hitler had planned to have the Reichstag pass a law making the Nazi Swastika flag the flag of the German Reich, and a major speech in support of the impending Italian aggression against Ethiopia.[119] Hitler felt that the Italian aggression opened great opportunities for Germany. In August 1935, Hitler told Goebbels his foreign policy vision as: "With England eternal alliance. Good relationship with Poland . . . Expansion to the East. The Baltic belongs to us . . . Conflicts Italy-Abyssinia-England, then Japan-Russia imminent."[120]

At the last minute before the Nuremberg Party Rally was due to begin, the German Foreign Minister Baron Konstantin von Neurath persuaded Hitler to cancel his speech praising Italy for her willingness to commit aggression. Neurath convinced Hitler that his speech was too provocative to public opinion abroad as it contradicted the message of Hitler's "peace speeches", thus leaving Hitler with the sudden need to have something else to address the first meeting of the Reichstag in Nuremberg since 1543, other than the Reich Flag Law.[121] On 13 September 1935, Hitler hurriedly ordered two civil servants, Dr. Bernhard Lösener and Franz Albrecht Medicus of the Interior Ministry to fly to Nuremberg to start drafting anti-Semitic laws for Hitler to present to the Reichstag for 15 September.[119] On the evening of 15 September, Hitler presented two laws before the Reichstag banning sex and marriage between Aryan and Jewish Germans, the employment of Aryan woman under the age of 45 in Jewish households, and deprived "non-Aryans" of the benefits of German citizenship.[122] The laws of September 1935 are generally known as the Nuremberg Laws.

In October 1935, in order to prevent further food shortages and the introduction of rationing, Hitler reluctantly ordered cuts in military spending.[123] In the spring of 1936 in response to requests from Richard Walther Darré, Hitler ordered 60 million Reichmarks of foreign exchange to be used to buy seed oil for German farmers, a decision that led to bitter complaints from Dr. Schacht and the War Minister Field Marshal Werner von Blomberg that it would be impossible to achieve rearmament as long as foreign exchange was diverted to preventing food shortages.[120] Given the economic problems which was affecting his popularity by early 1936, Hitler felt the pressing need for a foreign policy triumph as a way of distracting public attention from the economy.[120]

In an interview with the French journalist Bertrand de Jouvenel in February 1936, Hitler appeared to disavow Mein Kampf by saying that parts of his book were now out of date and he was not guided by them, though precisely which parts were out of date was left unclear.[124] In March 1936, Hitler again violated the Versailles treaty by reoccupying the demilitarized zone in the Rhineland. When Britain and France did nothing, he grew bolder. In July 1936, the Spanish Civil War began when the military, led by General Francisco Franco, rebelled against the elected Popular Front government. After receiving an appeal for help from General Franco in July 1936, Hitler sent troops to support Franco, and Spain served as a testing ground for Germany's new forces and their methods. At the same time, Hitler continued with his efforts to create an Anglo-German alliance. In July 1936, he offered to Phipps a promise that if Britain were to sign an alliance with the Reich, then Germany would commit to sending twelve divisions to the Far East to protect British colonial possessions there from a Japanese attack.[125] Hitler's offer was refused.

In August 1936, in response to a growing crisis in the German economy caused by the strains of rearmament, Hitler issued the "Four-Year Plan Memorandum" ordering Hermann Göring to carry out the Four Year Plan to have the German economy ready for war within the next four years.[126] During the 1936 economic crisis, the German government was divided into two factions, with one (the so-called "free market" faction) centring around the Reichsbank President Hjalmar Schacht and the former Price Commissioner Dr. Carl Friedrich Goerdeler calling for decreased military spending and a turn away from autarkic policies, and another faction around Göring calling for the opposite. Supporting the "free-market" faction were some of Germany's leading business executives, most nota

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home